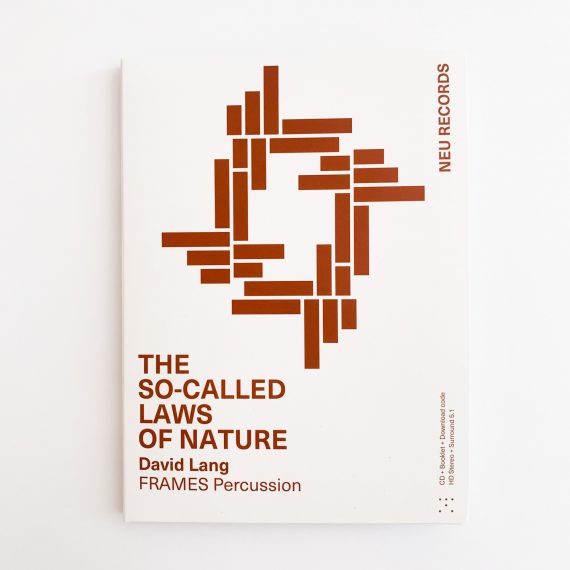

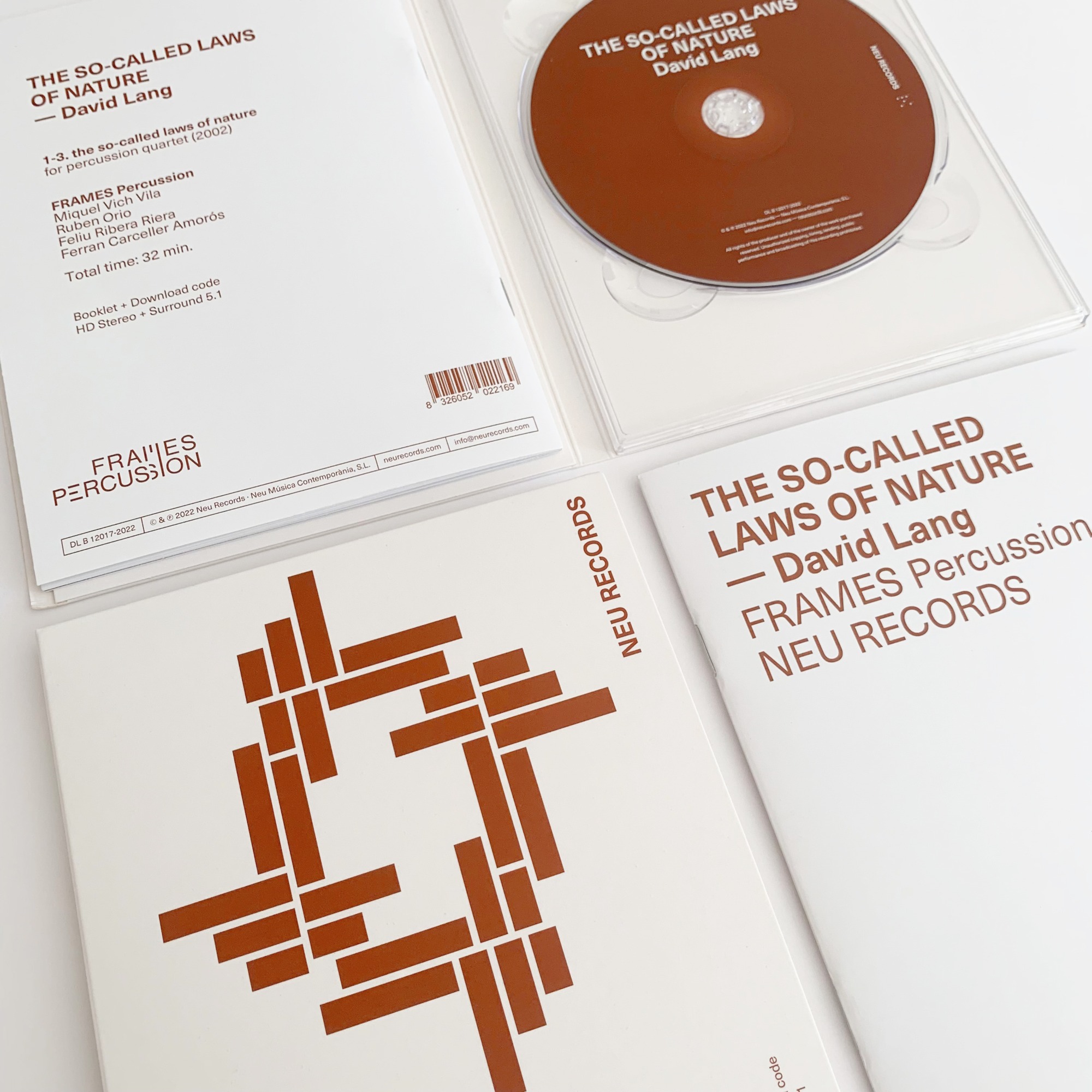

DAVID LANG

the so-called laws of nature (2002)

for percussion quartet — 32 min.

FRAMES Percussion

Miquel Vich Vila

Ruben Orio

Feliu Ribera Riera

Ferran Carceller Amorós

Recorded in 3D format for sound installations (5.4.1), surround sound (5.1) and stereo (2.0)

“The performance by Frames Percussion is amazing, the recording is sparkling and crystal clear.”

David Lang

BUY ALBUM

CD + Booklet — HD Digital format included — 21,90€

HD Digital — Stereo and Surround 5.1, 24bit 96kHz — 14€

Digital — Stereo, 16bit 48kHz — 10€

More info about formats here

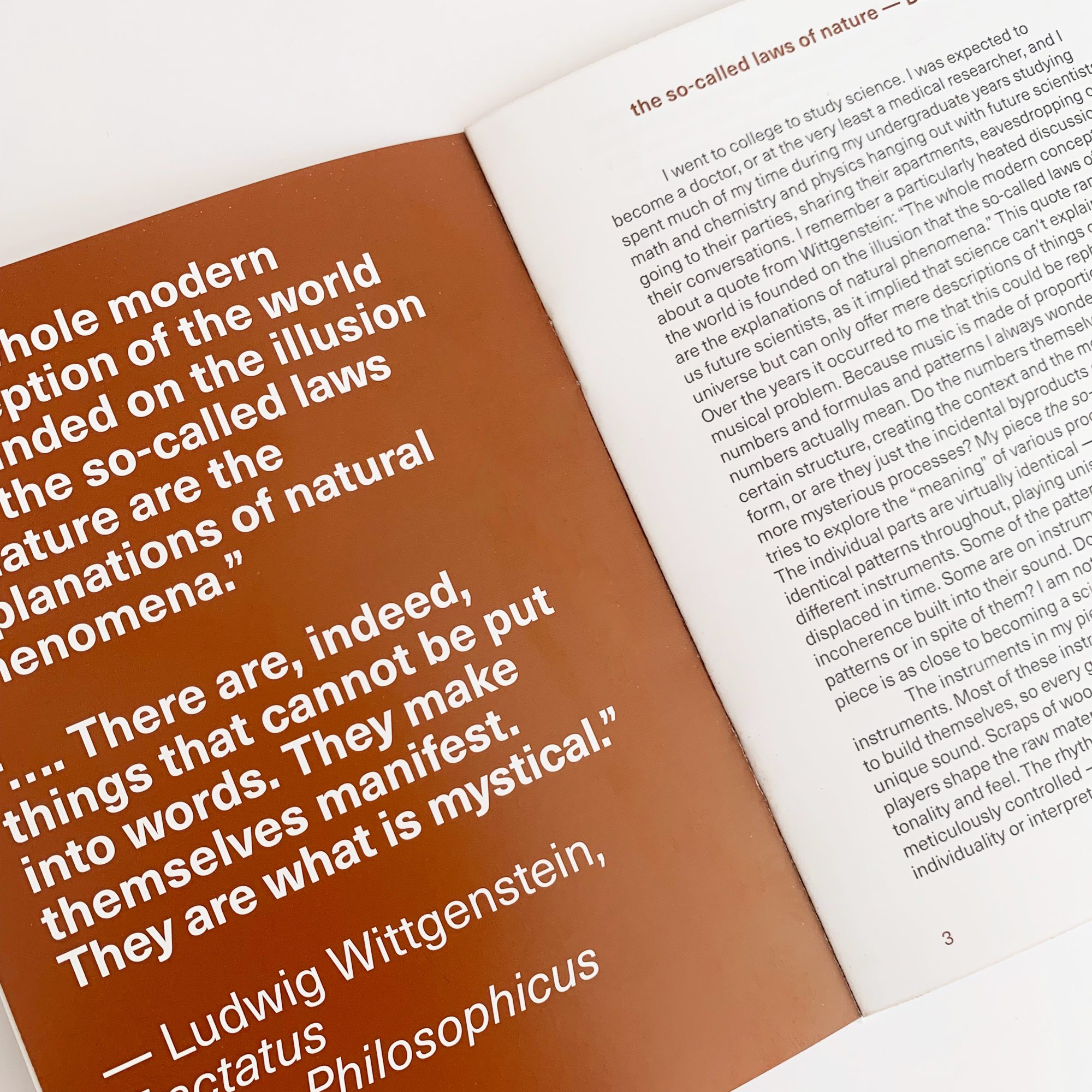

“The whole modern conception of the world is founded on the illusion that the so-called laws of nature are the explanations of natural phenomena”

Ludwig Wittgenstein

THE SO-CALLED LAWS OF NATURE

I went to college to study science. I was expected to become a doctor, or at the very least a medical researcher, and I spent much of my time during my undergraduate years studying math and chemistry and physics hanging out with future scientists, going to their parties, sharing their apartments, eavesdropping on their conversations. I remember a particularly heated discussion about a quote from Wittgenstein: “At the basis of the whole modern view of the world lies the illusion that the so-called laws of nature are the explanation of natural phenomena”. This quote rankled all us future scientists, as it implied that science can’t explain the universe but can only offer mere descriptions of things observed. Over the years it occurred to me that this could be rephrased as a musical problem. Because music is made of proportions and numbers and formulas and patterns I always wonder what these numbers actually mean. Do the numbers themselves generate a certain structure, creating the context and the meaning and the form, or are they just the incidental byproducts of other, deeper, more mysterious processes? My piece ‘the so-called laws of nature’ tries to explore the “meaning” of various processes and formulas. The individual parts are virtually identical –the percussionists play identical patterns throughout, playing unison rhythms on subtly different instruments. Some of the patterns between the players are displaced in time. Some are on instruments which have a kind of incoherence built into their sound. Does the music come out of the patterns or in spite of them? I am not sure which, but I know that this piece is as close to becoming a scientist as I will ever get.

The instruments in my piece are not standardized musical instruments. Most of these instruments the performers are required to build themselves, so every group will end up having its own unique sound. Scraps of wood, pieces of metal, clay pots –how the players shape the raw materials creates the piece’s sound world and tonality and feel. The rhythms in my piece are all strictly notated and meticulously controlled –there is not much room there for individuality or interpretation. It is in the choice of sounds that each performance can have some room for interpretation, some room to be expressive. That is where each ensemble’s personality will be found.

I am very excited about this recording of ‘the so-called laws of nature’. The performance by Frames Percussion is amazing, the recording is sparkling and crystal clear. Most of all I am happy that it sounds so different from the recording by Sō Percussion. I wrote ‘the so-called laws of nature’ for Sō Percussion and their recording is also great –I was at their recording sessions and I watched over everything as it was happening, and their recording was released on Cantaloupe, the label that I co-own. And yet, the piece, by design, has a huge range of options available to the performers, and I am happy that Frames Percussion has explored them, so thoroughly, and so well.

DAVID LANG

UNPACKING ‘THE SO-CALLED LAWS OF NATURE’

by ADAM SLIWINSKI, Sō Percussion

The so-called laws of nature was written for Sō Percussion in 2002. When we premiered it at the Miller Theatre in October of 2002, I was 23 years old. To this date, it remains one of the most enigmatic, exhilarating, difficult, and powerful pieces I’ve ever been involved with.

The piece presents a realm that at first seems rational: processes and forms unfold with aural transparency and systematic rigor. An eager student or performer may start analyzing and dissecting these structures, but will find that they do not always follow their own implied laws and behaviors.

In this article I’m going to unpack the so-called laws of nature just a little bit. As with nature itself, I can only offer a window into its complexities, not describe it totally. After twenty years and dozens of performances, I’m delighted to say that it still poses questions I cannot answer.

This article originally appeared on my blog in 2013. I’m happy to revise it in 2022 for the fantastic recording by Frames Percussion.

THE INSTRUMENTS

The so-called laws of nature is written for percussion quartet, which in reality means “either an acknowledged percussion instrument, something you make yourself, or a non-percussion instrument that you want to use in a particular way.” In this case, most of the instruments are homemade or found. Certain specific guidelines are given, while some amount of variation is allowed and expected.

The first movement is for seven woodblocks in each setup. No pitches are specified, but it still contains a fascinating tuning scheme: the top three blocks on every player’s instrument are exactly the same, with each block tuned progressively lower down the line. Player one has the highest blocks 4-7, while player four will have the lowest.

We play the first 222 bars in complete unison. But when I say “complete unison,” remember that the woodblocks (actually slats of walnut in our version) are not tuned in absolute unison respective to each other. This means that the top three notes are the same pitch, but each progressively lower note will sound as a complex chord which spreads wider apart the lower it goes.

Only six of the seven notes appear for the first 200 bars. That’s because Lang delays the arrival of the most extreme low chord until almost the end of the section, in bar 203. Most of the figures in this section cascade from the top of the instrument to occasional notes near the bottom, and those low notes are tuned further apart. The very nature of the instrument determines its sonic and structural characteristics. Reading the score doesn’t necessarily give you that information – it just looks like a stream of linear notes.

In the second part of the first movement, the tuning scheme allows the compositional texture to be flipped upside-down. Lang switches the main activity to the low blocks, with high blocks peeking out as accents. This means that the churning activity in the low blocks is harmonically muddled and complex – remember that these pitches are maximally spread – while the high accented blocks echo each other.

The second movement divides the players between homemade metal pipes and more traditional percussion instruments: tom-toms, bass drums, and brake drums. Brake drums, of course, are car parts and so closer to the “homemade” category.

The metal pipes are tuned to specific pitches that one could pluck out on a piano: F, Ab, C, Db, F, G, Ab (in the world of f minor). Each musician has the same pitches in the same register. They all play the same material, but in a constantly shifting series of four-part canons that strain the capacity of the performers.

In the third movement, Lang calls for tuned flowerpots, teacups, woodblocks, little bells, and guiro. Most of the instruments in this movement function the way percussion instruments often do: they fulfill gestural and rhythmic functions.

But the flowerpots are tuned to – which usually means “found at” – recognizable diatonic pitches. They undulate a steady chorale throughout the movement. Though they are notated and played as quick rhythmic figures, the effect is a smooth, sustained harmony.

One could conceivably play this chorale on many different instruments, but there is a fragility and an earthy quality to flower pots that cannot be replaced. It would not be the same on any other instrument. Though the performer must concentrate on a very difficult sequence of notes, the aesthetic effect is delicate, sad, and interminable.

“I am interested in perceptible processes. I want to be able to hear the process happening throughout the sounding music (…) To facilitate closely detailed listening a musical process should happen extremely gradually”

Steve Reich

PROCESS AND EXPECTATION

I.

The evolving teacup melody in the third movement of the so-called laws of nature is a great example of Steve Reich’s “music as a gradual process.” It displays mathematical complexity, and is very cleverly constructed…but you can also easily perceive elements of change as they occur.

“Gradual processes” have been around at least for the 900 years since Leonin and Perotin wrote choral pieces that required twelve minutes to sing two words. A gradual process is a fascinating way to construct expectations. Satisfying or thwarting the expectations implied by repetition and slow change is one of the composer’s sharpest tools, just as Mozart used tonal expectations and harmonic structure to sculpt his dynamic sonata forms.

In the third movement of the so-called laws of nature, David creates a counterpoint of processes. The teacup melody is the first one. Soon, little bells and woodblocks each proceed at their own pace through similar journeys, all managed by the performers’ linear dance while the teacups continue to spin along.

In a composition for quartet, you might expect any complicated layers to appear as distinct voices. In movement three of the so-called laws of nature, what you have instead is all four percussionists playing in unison, with only a split flowerpot voicing to distinguish them. This is a strange conceit, especially if you imagine any string quartet doing the same thing.

The second movement combines very satisfying gradual processes with much smaller ones. The opening bars articulate one of the most important ideas in the entire piece: expansion and contraction. This accordion-like gesture begins on only one note, F, and continues to build in ever-growing layers of complexity throughout the movement. It echoes both the motion of the teacup melody from the third movement and the accelerating/decelerating rhythms of the first movement.

These are very brief processes, concise enough to count as motives. The gradualness occurs through a slow accumulation of melodic material. The seven pitches of the tuned metal pipes are introduced slowly, creeping methodically up the scale, where their own expanding and contracting behaviors begin to collide with the pitches that have already been introduced. In a sense, this creates a classic contrapuntal situation, but instead of introducing the fugal subject at the fifth, Lang re-introduces the expanding and contracting figure on the next note.

As that momentum builds, the melodic tapestry eventually encapsulates all seven pitches, with the entrance of the three highest notes marking the halfway point of the pipe music.

II.

I once emailed Steve Reich about something that was troubling me in his seminal piece Drumming. I had been touring and teaching the piece a lot with Sō Percussion, and was puzzled by the patterns at the end. Instead of repeating exactly the same motives at a different rhythmic interval, he left a note out of each final pattern.

I don’t have the email anymore, but it went something like this:

Me: “Hi Steve, I wanted to know if there’s a mistake at the end of Drumming in the score. Players 7-9 each have one fewer note than the players that have already built their patterns.”

Reich: “No, it sounds much better that way, don’t you think? It’s too heavy if you put in the whole pattern!”

This was an incredible lesson for me. When I wrote my graduate thesis on Iannis Xenakis, I found his music also riddled with process-interrupting and seemingly arbitrary artistic decisions. In each case, I realized that they heightened the aesthetic impact of the moment.

After all, “Music as a Gradual Process” had said nothing to the effect of “change stuff whenever it sounds better.” I had imagined that a monolithic statement like Drumming would require some kind of dogmatic purity in its execution. For all the usefulness of systems to a composer like Reich, they were always the means to an end, and not the end in itself.

One of the most penetrating ideas in the so-called laws occurs in the third movement. As I explore below, the movement is perfectly symmetrical in form. But there is a hitch, a guiro that interrupts the smooth flow of the interminable flowerpot chorale.

After the first half is over, the piece feels like it could be complete — actually, applause often erupts during the silence before the second half in live performance. That it does so is a testament to the cohesion of Lang’s form. The guiros scrape out of that silence into the second section, which is a repeat of the first with guiros and woodblocks added (woodblocks now return to end the piece after starting it).

At the realization that the movement is only half over, some are delighted, others possibly dismayed. The full process takes a while – about six minutes – to cycle through. Our expectations of a peaceful resolution are thwarted, devastatingly so. In addition to the woodblocks that now chirp on top of everything else, the guiro becomes an insistent noise, disruptive and crass.

Right before the bells enter, the guiro succeeds in abolishing all of the old elements: only it and the woodblock remain for two measures. By scraping into the next phrase, it then gives permission for them to return after the rupture it created. Finally, the guiro has the last word, eventually silencing the entire melancholy chorale.

Even as I write this, I marvel that such a simple, noisy thing as a guiro scrape can stimulate such interpretive reflection. It is one of David’s true gifts as a percussion composer.

SYMMETRY AND FORM

On the micro scale, the so-called laws of nature manifests extremely subtle and complex processes. On the large scale, its structures are symmetrical and consistent.

Each movement is split exactly in half. In the first movement, the material changes noticeably from first to second part, and each half is about 450 bars. In the second and third movements, the music from the first half repeats verbatim, though with important differences. In the second movement, each half is about 300 bars, and in the third each is about 100 bars.

This literal repetition with variation hearkens back to Baroque forms with repeats, where a performer was expected to vary and embellish during the second repetition. The second half of the second movement cycles right around to the beginning of the pipe music, but with a significant new element: drums. They enter one at a time down the line at exactly the same point as each of the new pipe pitches.

Part of the extraordinary difficulty of playing this movement is that the performer must juggle multiple processes at the same time which have nothing to do with each other. They display the same behavioral characteristics, but do not line up in a predictable way, which means they must be practiced for a very long time.

It might have seemed from the bar-counting that the first movement is gargantuan, while the last is tiny. In fact, each movement progressively compensates for having fewer measures by also having a slower tempo. The six halves of the three movements all come out between about 5 minutes and 6 minutes in Sō Percussion’s recording. The first movement has some difference between the two halves, while in the second and third the literal repetition means they are almost identical.

There is one element in this piece that doesn’t insert itself logically according to the bi-fold symmetry of each movement: the climactic entrance of brake drums and bass drums in the second movement. Undoubtedly, this is the climax of not just the second movement, but of the entire piece. It arrives at measure 537 out of 620, 85% of the way through the movement. In the context of the whole piece, it occupies a different position.

In Sō Percussion’s recording, this cannon-blast climax occurs at about minute 22 out of 34 overall minutes, a point that corresponds neatly with “golden section” type structures. Whether or not it fits that model is irrelevant – what is more fascinating is that the overall three movement work, for all of its internal symmetry, also has a meta-climax that arches across the three movements with its six sections.

DRAMA

One of the trademarks of performing the second movement is the way we stand in profile, with each player’s back to the others. In this way it resembles a bass drum line from a marching drum corps. This is certainly not the easiest way to play it.

When we first received this piece, we set the second movement up in an arc. That way, we could see and hear each other most easily: as the first player, I kept tabs on each other player as the canons cascaded inexorably down the line.

Lang wasn’t satisfied with the convenience of this setup. He wanted his gradual processes to be not only well played and aurally satisfying, but visually striking as well. He asked us to make this profile line, where I as player one can’t see anybody at all! This means that not only is it harder to play together, but I have a difficult time distinguishing who is playing what behind me.

A large chunk of the first and third movements – actually all of the third – are in unison. Theoretically, so is the second movement, but we are offset in canons the whole time. By facing down the line to the side of the stage, the audience sees our mallets activate like pistons in a machine, always 1234 1234.

When the drums come in halfway through, their individual processes are just as visually transparent, because each performer’s left hand is easy to follow (I am facing stage right, so my left side is toward the audience). When the drums come into climactic unison, their visual consonance is extremely dramatic against the still-churning 1234 of the pipe canons.

David’s sense of the theatrical is highly developed in his percussion works. He seeks to accentuate and highlight the natural physicality of percussion playing. What I find so thrilling is that this serves more to highlight the processes and laws of his compositional universe than the personal expression of the performers.

In this sense, he doesn’t indulge in the sentimental with his subject. I don’t interpret the so-called laws as an emotional reaction against the rationalism of the scientific worldview. It is a celebration of it, but with a humble and mischievous acknowledgement that still greater mysteries lie behind the patterns.

ADAM SLIWINSKI, Sō Percussion

CREDITS

Recorded at

Auditorio de Zaragoza, Spain

July 2015

Composed by

David Lang

Performed by

FRAMES Percussion

Miquel Vich Vila, Ruben Orio, Feliu Ribera Riera, Ferran Carceller Amorós

Sound

N Music Production · Santi Barguñó, Hugo Romano Guimarães

Music editing assistant

Luis Codera Puzo

Liner notes

Adam Sliwinski, David Lang

Graphic Art Direction

Lorena Alonso. Estudio Gerundio

Mixed and mastered with

Dynaudio speakers

Produced by

Santi Barguñó

The so-called laws of nature · Album Images

David Lang, Frames Percussion, The so-called laws of natureDavid Lang · Photos

David Lang, The so-called laws of natureREVIEWS

“En aquesta nova obra del compositor barceloní, amb una vasta formació cultural, hi ha ressons dels quatre-cents pèndols del Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time (‘Enlloc i a tot arreu alhora’), de William Forsythe, o la Pendulum Music (‘Música del pèndol’), de Steve Reich; posant-hi un bri d’ironia, també hi afegirem el famós pèndol de Fellini. Rumbau, però, va més enllà i organitza el seu material sonor —processos, materials, textures— a partir de xarxes d’algorismes, sempre mantenint latent l’organicitat, un dels conceptes més estimulants de la seva creació.” Read here